AN HEIRLOOM FROM THE FLIPSIDE

A family heirloom rediscovered.

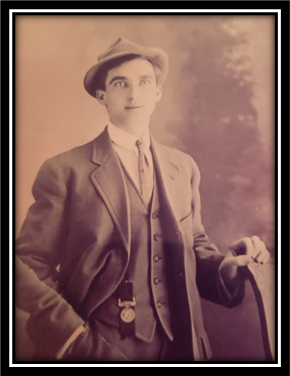

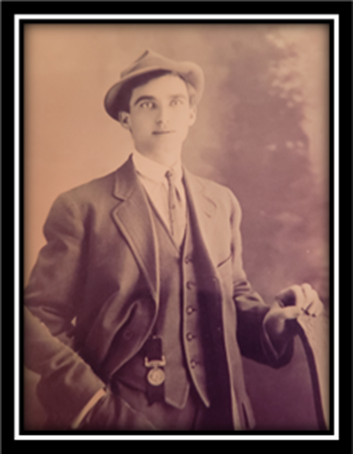

I ran across a photograph of this family heirloom the other day. The first photograph is my Italian grandfather Valentino Martini wearing the medal sometimes in the early 1900’s; perhaps his wedding day in 1915. I forgot about this medal until someone on the flipside suggested there was an “important photo of a man wearing a hat, holding the back of a chair.” This is the only photo like that I am aware of in our home — when my wife showed the medium the photograph, the medium said she got “chills from it.”

So I looked closer at the photograph. He’s not wearing suspenders, but a medal. I recognized it as a medal my father kept in a safety deposit box for decades. When the box was emptied, and the movers moved the contents of the house, one of the movers stole the medals in that box (and my parents jewelry and diamonds.) So somewhere in a pawn shop in the Windy City rests these three medals and diamond rings. I did my best to recover them — but one day while accessing my father and asking about these things, he said “they are where they need to be.” So I let it go.

However, the conversation with the medium prompted me to look again at this photograph of my grandfather Valentino. He’s wearing the medal that was in a safe deposit box, along with my Irish grandfather Edward A Hayes “National Order of the Legion of Honour” that was awarded him by the French government. Medals that were supposed to be family heirlooms. I knew what two of them were, but not the third.

Here’s a photograph of the more famous French medal from Edward A Hayes:

I’ve been the the Museum of the French Legion of Honour in Paris, where they verified he was awarded it, and in what year, but could not tell me anything else about it. The award is not given to many, but my grandfather Edward Arthur Hayes was awarded it during his lifetime of service in the U.S. Navy as a Commander and Assistant Secretary of the Navy during World War II. However, I assume it was given to him when he visited Paris in the 1930’s as National Commander of the American Legion. I have a postcard of Notre Dame that he wrote to my mom during that trip.

Another medal in the box, was unknown. But thanks to the internet I’ve been able to identify it as the “Commander of the Crown Medal” from Italy — given by the King of Italy, but I suspect this was given to my grandfather when he visited Rome as National Commander of the American Legion on that same trip. I have a photograph of him being saluted in front of the Victor Emmanuel Monument in Rome surrounded by military, including a crowd of black shirted Mussolini pals. (Circa 1934). Later, my grandfather orchestrated the surrender of the Italian Navy with Bill Donovan in 1943. But I suspect he got the Italian medal from that trip to Rome in 1933.

Commander of the Crown Medal (Italy)

USN Commander Ed A Hayes, far right, behind black hat Italian.

It was the “First national Order instituted after the unification of the Kingdom of Italy. This Order was conferred upon Italians and foreign citizens, regardless of religious affiliations, who had rendered extraordinary service to the Kingdom of Italy and the Sovereign within military and civil realms.”

Apparently the King of Italy gave him this medal in 1932. Oddly enough, some years later, my brother Robbie and I were having lunch in Rome with old friend Mirko Frattura’s father, who was an Admiral of the Italian Navy during the war. He was still a happy fascist, made a few snarky remarks about having to surrender to Americans, and offered that he tried to sink the ship the Americans were on — firing upon it instead of surrendering in 1943.

I had the odd moment of laughing, then saying “Well Signore, I’m glad you missed the ship, because it was my grandfather on that ship who accepted the surrender of the Italian Navy, your surrender.” Something he’d orchestrated with the help of “Wild Bill” Donovan of the OSS.

But I digress.

Alongside these two shiny medals was another flat brown medal, which reads “For the defense of Cadore” (ai defensori del Cadore) and has the date; 1848.

I’m familiar enough with our family tree to know that the name Valentino has been passed along for generations — and that the father of my grandfather was Alfonso (who came to the US in the late 1880’s) but that it was likely his father, another Valentino who earned the medal.

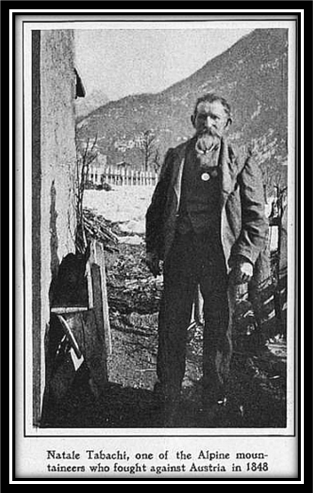

So I used the net to search the term “Ai defonsori del Cadore” and imagine my surprise to find a description of the battle that took place for people to earn this medal and published in Harper’s Weekly in 1911. The man interviewed was “Natale Tabachi.” He recounted his story and later, Robert Shackleton included it in his book “Undiscovered Places of Old Europe.”

Fun to find the entomology of anything that happened over 100 years ago. This is where the medal came from in 1848, and how it was passed down in my family. This is an excerpt from that book, in the Chapter “A William Tell of Unvisited Mountains.”

(Excerpted from Robert Shackleton’s book “UNVISITED PLACES OF OLD EUROPE” (Penn publishing 1922) Originally an essay for Harper’s Weekly (1911).

Chapter 17. “A WILLIAM TELL OF UNVISITED MOUNTAINS”

“One of the most interesting of all the Italian towns of the Dolomites is Pieve di Cadore. It is a small and compact place, a village set upon a hill, with houses large, of stone, with wide-projecting eaves. It is a charmingly situated and very ancient town, whose name, Italian fashion, has the softly musical pronunciation, with the accent on the second syllable of each three-syllabled word, of Peeavay dee Cadoray.

While at Pieve, which is over the border in the Italian Alps, Cortina being Austrian, it came to me that hereabouts there was much fighting back in the troublous times of 1848; that in this region the Alpine mountaineers fought to recover their freedom and overthrow the Austrian dominion, as they did in the days of William Tell; and that this race were Italian instead of Swiss, and were fighting not for Swiss government, but to re-establish that their beloved Italy, did not in the least lessen the fascination of it all, nor its strange resemblance to the picturesque warfare of centuries ago.

A large part of these Eastern Alps is Italian. For generations the people of this region have been Italian in race, in tradition, and in feeling, but by the division of Europe which followed the Napoleon wars this part of the Alps was given to Austria, regardless of the feelings of the inhabitants.

But In 1848, that year of revolutions in Continental Europe, came the opportunity to rebel, and these Alpine mountaineers rose against the Austrians, defeated them, and regained from them much of the mountain territory. The picture of it all grew more vivid to my fancy, Alpine mountaineers fighting here against the Austrians, as in the days of William Tell, yet within the memory of men now living! and with this thought there came another.

Here, where I was visiting an unvisited Switzerland, how fascinating it would be if I could actually find some ancient veteran who had fought, more than sixty long years ago, just as the early Swiss patriots fought six hundred long years ago! Instantly I sought out the landlord. “I should like,” I said slowly, “to talk with some old man who fought here in 1848 against the Austrians.”

His round face lengthened into doubting gravity. “But is there such a man?” he asked.

“Surely,” I replied, with matter-of-fact confidence. He was silent a few moments. Then: “If the signor can wait, I shall inquire/’ he said. And I thought, as I have often thought, how delightfully helpful a European landlord can be! He sought me out in the town in an hour or so, and said that he had learned of a ’48 veteran living in a village in another valley.

“With delight I shall lead you there,” he said, beaming as he saw how much he had pleased me, “But” with a touch of doubt “It is to walk! it is a mountain path and the snow “ I reassured him as to the walk and the snow, and we set off together over the mountain, and reached a tiny hamlet, a huddle of ancient stone houses, precariously clinging midway against a mountainside with a precipice dropping far down in sheer abruptness in front, and the mountain towering rugged and steep far above.

He led me to the ancient veteran’s ancient house, where the old man greeted me, his eyes glowing with happiness. “Buon giorno,” he said. He tried to draw up his stiff form with soldierly dignity. “I am Natale Tabachi,” he said; and then, with pride: “You would have me tell of the fighting?”

We sat down in a low-ceilinged, heavy-beamed room, around a fireplace of the ancient type, built out in the very center of the room, with open space all around it. We sat down in or rather climbed up on chairs with stilt-like legs, made thus high to permit of putting one’s feet on top of the fireplace hearth, and the veteran beamed expectantly.

But I knew that this was not a case where some slight understanding of ordinary Italian words would be satisfactory, so I said to the landlord: “This is delightful; and now I should like someone who can translate for me.” His round face lengthened. “But is there such a one?” he asked. “Surely,” I replied. He was silent for a few moments. Then: “If the signor can wait, I shall inquire,” he said.

And within fifteen minutes he was back, proudly leading a young Italian who had only the week before returned to his native home after three years spent in Boston and New York! And then, in that ancient house at the very edge of a precipice, a house looking over a superb view of valley and, mountains, we talked together. “I have never before talked with any but my own people,” he began; and I was glad, for it assuredly made him an unvisited mountaineer among these unvisited mountains practically unvisited even in summer, this village, set off as it is from the tourist track that reaches to Pieve.

Gradually the old man warmed eagerly and more eagerly to his subject, as old-time memories came charging to his mind, and his old voice trembled with emotion.

“I live among these mountains. They are my home. It was among these mountains that I was born; I, Natale Tabachi.”

Natale Tabachi photo in original Harpers Weekly 1911 (vol 55)

“And it is here that I shall die. But although I was born as a subject of Austria I shall go to my grave as a free man.”

“It was long ago that I was born. I am old, and it is easy to forget. But see here are my papers. I was still a young man when we fought the Austrians in 1848.”

“I do not forget that date. No! For here, on my medal, it is set down. Do you see? Will you read it to me?

‘Ai Difensori del Cadore, 1848?’ “Yes; that is it; for I was born a man of Pieve de Cadore and I fought for it against the Austrians. Do you wonder that I love this old medal and its little ribbon of green and yellow?”

“We are Italians, we; and why should we be under Austria? Italians, all; and our fathers and their fathers were Italian. And we did not like it that the Austrian flag flew over the forts among our mountains. Why should the Austrians hold our great Alps and our valleys and our villages because kings of rulers far away said that the line of boundary should be so and so and so?”

“In the year that was to have the great fighting there was much unrest. Men gathered and talked and said, ‘ There will be changes.” And rumors came of unrest in the land, and again men said: “There will be changes here. We will not be under the Austrians.”

“And other men came among us from the South, and quietly they went about, and it was not long before we said that we would be free and that we would no longer obey the Austrians. I do not remember all. I am old and there is much that I forget. But I well remember that we were to fight the Austrians and that some of us were hunters and had guns, and that for others there were guns that came from Venice.

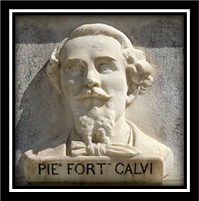

And we were gathered together in bands. “Our leader was the Capitano Calvi. “A man of fire, he! A soldier! He was not of these mountains, but was an Italian of the South. I do not remember just how he came to us, but only that he came and was our leader and that we obeyed him with gladness, for he was a brave man and he knew the rules of war. A young man, too: perhaps thirty, perhaps a little more; slender and tall and with a long mustache upon his upper lip; and with eyes that flashed.”

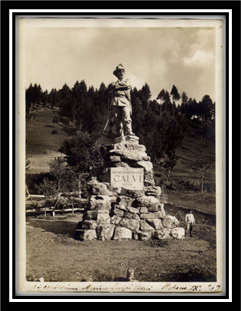

Pietro Fortunato Calvi

So we gathered in the mountains and we knew that the soldiers would come against us. A few said, ‘They will not dare to come.’ But the most of us, we knew that was foolish, for of course the Austrians would not go away without trying to kill us. “

“We had no uniforms. We were dressed just as we worked in the villages and on our land. But we could shoot and we would not let the Austrians stay with us. “I had often seen the soldiers. Well did I know the tall hats and the straps across the breast and the knapsacks and the guns.”

Often had I said “Buon giorno” when I passed them in the road. But never had I thought to fight them.”

“So we gathered; and one day it was in May, we were near Chiapuzza. You know the place? (Near San Vito Di Cadore) And the valley is very narrow there, with great heights of mountain, for always the Capitano Calvi; he chose such places for us.

San Vito Di Cadore

And, indeed, as you have seen, there is little in this land but great mountains and great depths. “

And we saw the Austrians coming up the valley. We looked, and we said, “There are two thousand of them.” We watched them, for we had often seen them march through the valleys when there was peace between us. We saw the high hats and the straps across the breasts and the guns.

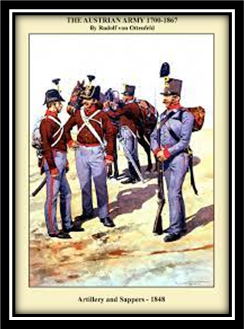

Austrians soldiers from 1848

“And the sun glistened upon the steel, for It was a bright and sunny day, and it was about the time of noon. I am old, and I forget much, but still there is much that I can remember.”

“Our guns were ready, but the Capitano Calvi had told us that we must not fire till we were told, and he was a man to obey. “

“We saw the Austrians stop; and perhaps two, three, I do not remember, walked forward with a white flag, and men said, “lt is peace, not war, and there will be no fight.’

And we were troubled, and we did not understand, and we were very silent as we watched, and we saw that the Austrians were met by our men and that there was talk. “

Afterward, men said that the Austrian leader had sent to tell us to throw down our guns and go home and be sorry and that there would be pardon, but that our Capitano he only laughed and he said, “We will fight.’

“And did I tell you that the women, many of our women, were with us? For they had said, ‘We, too, will fight.” And each of the women had her great field-fork. You have seen them?

And each of the women was strong. For our women, they work in the mountain fields and carry heavy loads and toss hay or straw with forks, and they are strong. “We had put the women behind us to fight if the Austrians came close. For they had said, “We will fight to save ourselves from the Austrians if they get past you.’

“And now they screamed, high and loud, those women yes, high and loud. Have you heard women scream when they would stab and kill? It is not a pretty sound. It is a very terrible sound.”

“For us men, to fight and to kill is a part of our lives. If it comes, it comes. It is right for man. But for women it is different. And they screamed, a laughing sort of scream, as the Austrian men were sent away, and the sound went back and forth among the cliffs. “

“And all the time the bells of the village were ringing. They were ringing fast and mad ringing, ringing, ringing. And in other villages the bells were ringing fast and mad, and the sounds came to us through the valleys. “The bells they rang so fast and so mad to make the alarm and tell all men to come and help us, and we knew that as they rang our friends and brothers were coming running over the mountains and through the valleys. “

“It was over sixty years ago, and I am old, and there is much that I forget, but never can I forget the mad ringing of those bells. It was a sound to make you weep, but also to make you grip your gun and know that you were ready to fight and to die. “

“Well, the messengers went back, and the women screamed, and even the boys who were with us to fight cried out, and when we men, watching so anxiously, saw that there was to be a fight, we too made a great, loud cheer. “

“The soldiers came on, but they were cautious and they came slowly. They fired at us from distances; and we aimed and we fired at them, for so the command had come to us. We aimed at the men just as we would aim at the chamois, but I do not believe we thought of that at all, even though we had often said ‘ “Buon Giorno” on the road.

“We wanted to kill, for we were hunting them, and whenever an Austrian fell we shouted for joy.” “For three hours, four hours I cannot tell we aimed and we fired, and the Austrians fired, and sometimes their bullets would hit a rock near us and send splinters.”

“But at last they had had enough, and they went off, sullen and slow, toward the north, toward the place from which they had come. They carried their wounded with them, but they left their dead, and we buried them. And, though they were young men, we felt no pity, for we thought only that we were fighting for our land. “

“Well, the war went on. And for days together, at a place a little farther south, we fought the Austrians again, and at night we would sleep just where we were, lying down on a rock or in the middle of the great pine woods, and always there were a few who watched to see that no soldiers came upon us in the dark, for so our Capitano told us, and he knew the rules of war. “

“Thus we would sleep at night, and in the day-time we would creep up the cliffs and climb over great rocks to watch the soldiers and to shoot at them. a And whenever an Austrian was hit and went falling, falling down, tumbling over and over like a great stone that had been rolled over the edge, we shouted for joy. “

“For the Austrians they burned our houses; they burned our villages; they killed our children. And they misused our women. And so it was that we shouted for joy whenever we saw one go tumbling and tumbling far down like a great clumsy stone. “

“So there, too, the Austrians could not pass us, could not drive us from our mountains, and for some days we marched and climbed and waited for them again. Often we were hungry. We shot a little game, but we did not like to waste powder and ball just for food to eat when we needed it for the Austrians. But our women they followed us up the mountain paths, carrying food for us, and we would build fires and cook our polenta and drink from the mountain springs and sometimes tell stories and sing and even dance.”

San Vito di Cadore mountains

Cadore Polenta and mushrooms

“But there was not much of that, for we did not know when the soldiers might come, and it was not well to make a merry noise to tell them where we were. “

“There was a priest with us, from one of our villages. He was an eager man and he said prayers over us, far up among the heights, and men would kneel before him for his blessing. And the priest often he would go before us and find a camping place, and he would say, just like a Capitano, ‘You will camp here. He was like a soldier that priest. An eager man, an earnest, eager man, and he said prayers over us and blessed us when we knelt. “

“There were many thousands of the Austrians, and they came against us from the north and from the south and from the east, so that we did not know which way to go. But our Capitano knew, and the priest knew, even though we did not know. “

Sometimes the Austrians attacked us in the night, but always our men who were on guard gave warning, and always we jumped up quick from where we were sleeping on the rocks or beside some fallen trees, and there would be a little firing and the soldiers would go back. “

“At last it was still in that same month of May, but many days had passed we thought they were coming at us from the south again, for at a place in the valley of the Piave, near a little town called Rivalgo, where the mountains are very high and the river runs swift through a narrow space, our Capitano made us barricade the road. With wood, with rocks, we built a barricade. And while some were building the barricade others were piling loose stones far up on the cliffs above, and others were undermining great rocks for powder to be put under them. “

The Piave River near Rivalgo Battle of the Piave from 1918 Pietro Fortunato Calvi

“All this did our Capitano Calvi order, and he was everywhere, and his eyes were flashing, and he was glad like a man who makes ready for a dance. There is much that I forget, but never can I forget our Capitano, and how he made us work to build the barricade and pile stones and undermine the rocks for powder. “

“At last there was better than building and piling and mining, for there was a cry, ‘The Austrians! They are coming!’ And every man went to his place, as our Capitano had directed, for he knew the rules of war. “

“The soldiers came on very brave, marching steady, steady, keeping step. Then they halted, and spread out across the narrow valley, and some were set to climb the rocks. And in all there were thousands of them. “

“We cheered and we fired, and we shouted when men fell; but the Austrians had a leader who would not easily give up, and his men all fired back at us, and more of them were set to climb the rocks. “

“And then we sent the stones rolling down, down upon them. The powder was exploded and the great rocks fell. And they struck the Austrians who were on the mountain-side, and many a man went rolling down with the rocks. And our men fired from behind the barricade. “

“And many rocks went down like live things, leaping from point to point and then springing down and scattering the soldiers in the road. “But even yet the Austrians would not retreat. We saw their officers urge them on, and the most active tried fast to climb above us on the mountain-side. But always we climbed higher and faster and always we fired our guns and rolled down stones. “

“I am old now, and my hands tremble and my voice trembles and it is hard to walk; but I was young then and could climb and shout and roll stones and fire my gun. “

“And at last they went back, they. Yes; the Austrians went back. And we shouted for joy, and we gathered around our Capitano and we shouted for love of him. “

“Their dead this time we did not bury. No. You have seen how swift is the Piave? You have seen how we men of the mountains float our logs in it, sending them down to the plains? Well, it was so that we did with their dead. We tossed them into the river, those men who had burned our villages and misused our women. We tossed them into the river, and we said, “You dead men, follow after the living.”

“And they followed fast, floating, bobbing, tumbling, in the swift waters of the river. “

“So it was that the Austrians could not beat us; for though we were not soldiers we could climb and shoot, and we were fighting for our own land, and our leader was a soldier who knew the rules of war.”

He paused for a long time, forgetting everything else in memories of those brave old days. Then he said very gently: “Men have said to me: ‘What was the use of fighting the Austrians? You are an old man and poor. How did it profit you?’

“Am I poor? I do not know. But I do not think so. “Here I sit in my house, on a comfortable bench, with my feet on the stone hearth built in the middle of the room. And is it not a pleasant heat that comes up from those logs? I have heat and I have shelter and I have food. Here, in this house, live my children. Here are also grandchildren. Soon there will be grandchildren’s children, and there will still be room, for we Italians are an easy and a friendly folk and there is always room. “

“And whether I sit in the warm sunshine at the door, or whether I look out of my window, I look up at great mountain slopes and I look down into this great valley at my feet, and I know that I, an Italian, am looking at Italian land. And on that fort, far up, is the flag of my country and not an Austrian flag!”

*****

(Robert Shackleton’s memoir continues) I returned to Pieve di Cadore even more ready than before to appreciate the dearly bought liberties and the broad-minded government of the town and the region round about, for I now understood that liberty and government had been fought for and maintained for generations by such men as this. The Sindaco of Pieve, the mayor, serves for five years. He is elected by the Council, which also has supervision of roads and taxes.

And the Council members are chosen by those men, over twenty one years of age, who can read and write. The Sindaco is paid only in honor. “Of course he has no salary,” is the way the people quietly express it. The explanation of all this being that Cadore was a real and vital republic long before America was discovered, and that the ancient influence still lives.

There are great forests, the property of the various communes, and lumbering is an active business. Tens of thousands of trees are annually cut and floated down the tumbling current of the Piave to the Italian plain. For centuries these forests supplied masts for the Venetian ships, and long before that gave masts to Roman galleys, and the Romans had a school of forestry here!

And several hundred years ago there was a threatened teamsters’ strike, which the Council of Ten settled by declaring that, of every hundred loads of wood, seventy might be floated by water, but thirty must be hauled. We need not think that labor troubles are new!

The people are happy. Wine is their water; every one dances, every one sings, every one plays some musical instrument; there are amateur theatricals; there are frequent holidays and feast days; there is the friendly clink of glasses and the still more friendly three-syllabled “Salute!”

There comes the memory of an evening at this town of Pieve di Cadore, when there was an unplanned after-dinner gathering in the large room that was ordinarily used only in the busy season. A piano stood there, and the landlord and his two pretty daughters drifted in, and two girl friends from next door, and two officers from the fort, and a councillor, and the bald-headed waiter, still with his napkin draped over his arm.

All at once the piano was playing, a mandolin was twanging, a violin added its notes. Another moment, and the pianist, one of the officers, jumped up and claimed the prettiest girl. The waiter, absent-mindedly stringing his napkin about his neck, slipped into the place at the piano and madly thrummed an infectious tune, while violin and mandolin hummed and tinkled in unison.

For an hour everybody danced or played. Everybody was spontaneously happy and natural. Pieve di Cadore was the birthplace of the mighty Titian, and upon the house is the admirable inscription: “Cadore points out to its guests the house where Titian was born.”

Titian — Pieve Di Cadore

Close by Is a statue of Titian, belatedly put up a few years ago; and a heavy snow so covered the head and mantled the shoulders as to make it absurdly simulate the appearance of the late Queen Victoria. The people love to talk of Titian. It is as if he flourished yesterday. He is the familiar glory of the place.

And I remember an old man who, clad in trousers of marvelously patched yellow and coat of marvelously faded blue, swept a comprehensive arm toward the forested mountains, the village dotted valley, the river down whose current innumerable logs were tumbling, whirling, plunging, rushing tumultuously, as he said: “ It was here that Signor Titian sawed wood.”

But there was no touch of frivolity in this; no Italian echo of a figurative Americanism; to him it was all very literal, very serious. “You are perhaps interested?” he went on, slowly. “Then it is with pleasure that I shall tell. The Signor Titian, he went from this, his home, to Venice, and there he painted pictures multo!”again he waved a comprehensive arm. “

“But always he kept his share in one of the sawmills of this valley; it was a rich mill with much of business, and it made him many thousand of lire. And every year Signor Titian came back here to his home. It was to see to the money and the business; for, look you, a man* must live. Life, it is not all the making of pictures!

And so he came here every summer time. It was also for the good air of these mountains, for it gave him the health and the strength. “And it was because, one summer, he could not get back here that he died. You have heard? For the plague, it broke out in Venice, and the soldiers had made a line and said that no man should go out of the city. And so the signor died there in Venice, instead of coming back to the mountains and getting more money and health and life.”

*****

It was in 1975 that I wandered into Pelos Di Cadore, a student going to school in Rome, armed with a postcard from his grandfather Valentino with the names of his cousins who remained in Pelos. I showed the card to a local woman, she said “Tutti sono morti!” (They’ve all died.) But she spotted one name on the card, and directed me to his fruit stand. I met his wife Irma washing vegetables, asked for her husband Giovanni Battista De Martin by name, and she called for him, “Titta!”

He walked out of the back room, said in English; “You’re Richard Martini, welcome home.” I had no clue how he could know who I was, but he said my grandfather had written to him six months earlier saying I’d arrive soon. He heard some American was “wandering around the town of Pelos” saying “Buon Giorno” to the locals, and he said; “You look just like him.”

I’ve met those family members, and our daughter just returned from visiting the ancestral stomping grounds. Families upon families, dating back at least until the 1600’s. I am reminded of my uncle Mario Vecellio, (Valentino’s first cousin) who was a direct descendant of Titian (Tiziano Vecellio) and the former President of Siemens Electric Company in Switzerland. Mario and his wife had lovely homes across Italy, in Positano, in Milano, but his favorite was in Pelos Di Cadore. And when Mario was near death, he hired an ambulance to drive him from Milan to Pelos, as he didn’t want to die without seeing his beloved home and the sparkling mountains once again.

If one gets a chance to hear the song “Bella Ciao” sung by an Italian, as I’ve heard many nights in Cadore, it brings to mind these beautiful mountains and the men who gave their lives to keep them free.

Point of this story is that the heirlooms we own (and have lost) all have some memory attached to them, and if we can tap into that energy or frequency, we can get a taste of what their lives were once like, even in a tiny village in the Alps near the border of Austria. A way of paying homage to their journey. A way of saying hello to someone who may be keeping an eye on us from the flipside.

Wonderful read! Thanks!

ReplyDelete